Dear friends and supporters:

I’d planned to finish this newsletter as “The Liberty Movement: COVID-19 and the divide between ‘The Anointed’ and the liberty-lovers” to post this weekend, but Sharon and I are headed out of town Friday, and I refuse to do a newsletter rush job. That article should be out by mid-next week

If you just signed up, you can read the first CultureChange: “The Virus and the Powers: The real COVID-19 battle is behind the scenes.”

Today I was interviewed on Apologia by Pastors Jeff Durbin and Luke Pierson on “Christian” Gnosticism. I showed how this ancient and most dangerous heresy survives today in large sectors of otherwise conservative Christianity. In fact, the modern church, both liberal and conservative, is awash in Gnostic tendencies:

Now for the main, if brief, event.

Recently I was talking to my oldest son Richard, who just completed his Ph.D. in philosophy at the University of British Columbia. He is also interested in theology. In fact, he is Junior (soon to be Senior) Scholar of Philosophical Theology at the Center for Cultural Leadership. He’s been researching the Trinitarian and Christological controversies in the theological development of the patristic church (era of the church fathers).

He was discussing how remarkably sophisticated and deep those arguments were on all sides. These church fathers were what we today call philosophers, not just theologians. In fact, the distinction between philosophy and theology didn’t emerge until later. Augustine, Athanasius, Irenaeus, and others are what we today call worldview thinkers. They weren’t only expounding biblical texts, essential though exegesis is. And they weren’t just creating a coherent theology of those texts. They were relating theology to the entire world, the universe, even. The best Christian thinkers since then have done the same thing.

For this reason, we can speak not only of church history and historical theology, but of Christian intellectual history. We might call it Christian historical worldview thought. Down through the centuries, Christian thinkers from Augustine to Aquinas to Calvin to Kuyper to Schaeffer showed how Christianity alone answered the great intellectual questions of the time, and of all times.

The ignorant secular intellectuals

I mentioned to Richard that two highly divergent groups today seem blissfully unaware of this intellectual history. First, there are secularists, particularly scientific naturalists, for whom any metaphysical reality is a myth. They look at Christians as knuckle-dragging rubes. Many of them seem to have no idea of the depth of Christian thought, and how that long before they came along, Christians were thinking about the very deepest issues of reality they rarely even consider, like the meaning of life, the mysteries of the world, transcendent bases for ethics, and much more. If anything, it’s the secularist worldview that is paltry and narrow, not the Christian worldview.

The dismissive Christian anti-intellectuals

At the opposite end of the spectrum, however, are many of the fundamentalists, who downgrade Christian intellectual history or, best, couldn’t care less about it. They seem to consider any Christian scholarship as a form of intellectual pride, and they’re constantly warning about the dangers of intellect, which will lead away from a warm-hearted devotion to Jesus Christ. (Strangely, they seem not to consider the dangers of emotion.) To their credit, many are Bible-believing people, but they don’t seem to understand that the Bible couldn’t have been translated and delivered into their hands apart from scholars. Translation requires a comparatively high degree of intellect, or at least intellectual work.

More significantly, they usually take for granted truths like the orthodox Trinity, which weren’t read straight out of the Bible but were the result of serious, painstaking intellectual reflection on the meaning of a synthesis of biblical texts and expressed in the best philosophical language of the day.

In short, without Christian intellectuals, we wouldn’t have the Bible, and we wouldn’t have the best formulations of our basic beliefs found in the Bible.

We all — intellectuals or not — owe a debt to Christian scholarship.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to CCL via PayPal or Venmo if you can. God uses you to keep us going — and expanding.

Personal

The April 6, 2020 issue of National Review carried a delightful article from an English professor about marking books. He mentioned his experience of returning to his notes in books he read even as a child and trying to decipher his annotations. Our book markings tell us something about ourselves, and at least about our former selves. I disputed the author on one point, and sent the following letter to the editor:

Dear Editor:

Graham Hillard’s lovely “At the Margins” resonated so deeply that one line counterfactual to my experience stood out: “Like having a child or planting a garden, annotating a book is an expression of hope for the future.”

Nearly 40 years ago my recent bride leafed through one of my books and said with disgust, “This is so marked up that nobody else could possibly read it.”

“Right,” I replied. “It’s my book, not somebody else’s.”

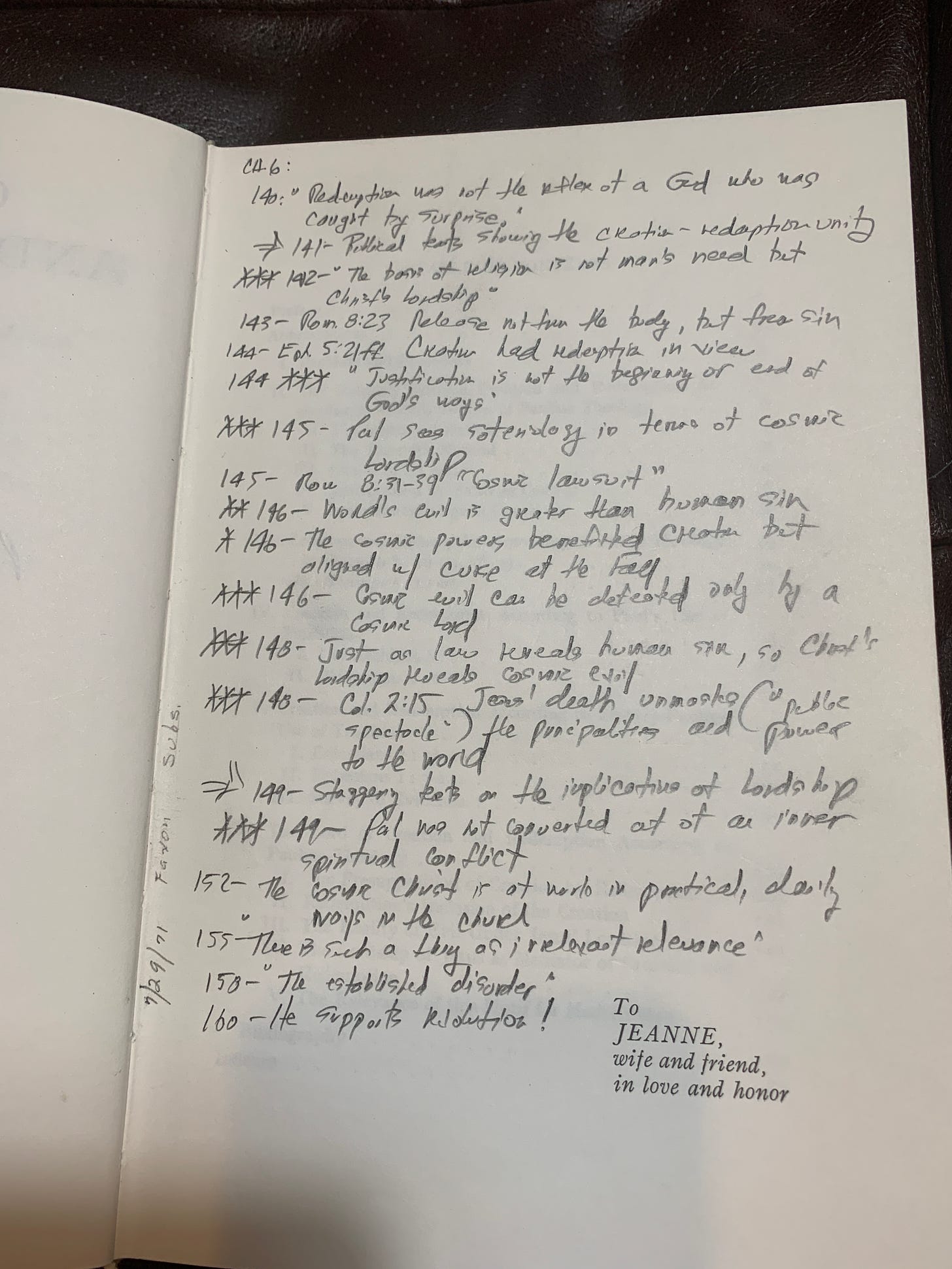

My books are copiously underscored, highlighted, dogeared, and too often spine-separated. My annotations fill the pages, and as a writer who can’t afford long, analog source searches, I duplicate them at every chapter head or in the fly leaves or inside the back cover. I then — just for good measure — handwrite the most memorable of those same annotations in my treasured leather-bound journals. It’s an aesthetic chaos only I can decipher.

When I die, most of my library will be useless for posterity. But that’s OK.

It’s mine, not theirs.

Much respect,

Here are annotations from a book I recently finished, John G. Gibbs’ Creation and Redemption: A Study in Pauline Theology —

Just a reminder that my Amazon author page (print and digital) is here. You can find my sermons and lectures at my YouTube channel. Sign up to get my blog updates here. Here’s my Twitter feed. If you want to get the free exclusive hard copy publication Christian Culture, please send me a Facebook private message. The CCL phone number is 831-420-7230. Finally, the address is:

CCL, P.O Box 100, Coulterville, CA 95311

If you know of anybody who might enjoy this newsletter and subsequent ones, I’d be grateful if you asked them to sign up here.

See you next week …

Yours for the King,

Founder & President