Friends,

The “new normal” for CultureChange is two monthly long-form cultural essays alternating with shorter book, movie, and TV reviews, or brief comments on cultural issues.

This is the short-form.

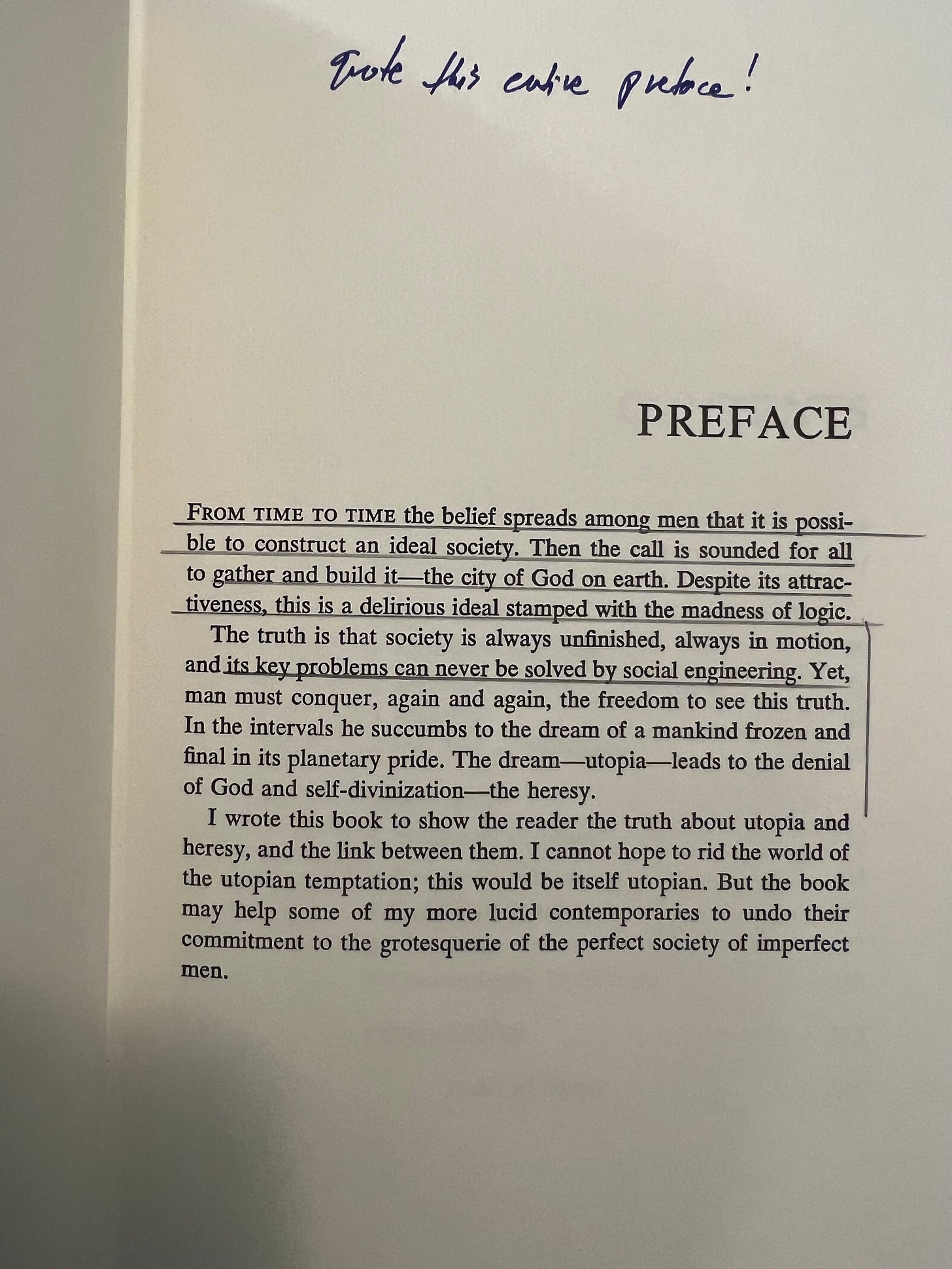

Last week, I wrote Utopia Unbound, in which I mentioned probably the best book about modern utopianism I’ve ever read, Thomas Molnar’s Utopia, The Perennial Heresy. His extended epigraph hooked me, and you can read it for yourself:

Here are only three memorable insights of this easily manageable 240-page book.

First, utopianism is a religious faith, the secularization of Christianity. Christianity promises perfection on God’s terms, gradually, through the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, though fully accomplished only in the eternal state. Utopians also believe in redemption and the perfecting of the present order, but man accomplishes it by means of politics. Politics occupies in utopianism the role the Holy Spirit occupies in Christianity. It is the engine of perfection. Therefore, to utopians the state is the new god. Because the God of the Bible is palpably anti-utopian, he is the main obstacle to utopianism. This is why all utopians must logically be atheists.

Second, note this:

What the utopian denounces is not so much evil in the moral sense but the impudence of a world which is content to exist full of flaws and defects — an ontological condemnation rather than moral (p. 6).

Utopia is not a sort of secular Puritanism, merely attempting to purge Christian “values” to be replaced by secular ones. Rather, it opposes the Christian idea of the world itself as fallen and in need of a redemption that can be fully accomplished only after the final judgment. The fundamental utopian premise is that the structure of the world is out of kilter, and man must remake the world. The universe itself is structurally flawed. This means that utopians are consistently at war with reality.

Third, consider the ecclesial dimension of utopianism. Molnar notes that it was the heretics that first stressed the priority of the “invisible church,” of which the deeply flawed visible church was a pale, pitiful reflection. There is a strong distinction between the heavenly and the earthly, the church being the heavenly people — the invisible church, of course, not the actual institutional church that meets on Sundays. The important thing is the elect, known only to God and, presumably, to one another; and these elect must avoid and if necessary eliminate the inferior, material, visible church. This is utopianism as it relates to the church.

There are dozens of other sparkling insights in this fascinating book. I hope that you can get it and read it.