Chronological Snobberies

"In so far as we speak or act, we can act or speak meaningfully only between two other generations, preceding and succeeding us, because we always come too late for ourselves…."

Dear friends and supporters:

Chronological snobbery might be described as (1) privileging a certain historical era or eras and/or a certain period of the individual’s life and (2) insolently de-privileging the others. There’s nothing new about chronological snobbery. There was plenty of it in the ancient world (including instances in the Bible), but as historical awareness has increased over the last two or three centuries, so has chronological snobbery. Here are leading examples. They are worth considering because they customarily become part of the individual’s worldview.

Modernist Snobbery

The modernist snobbery is built on the premise: whatever is later is better (Kenneth Minogue). Everybody knows (or is supposed to know) that the iPhone 14 is superior to the iPhone 4, and, similarly, the ethics of 2024 — including gay “marriage,” cancel culture, and gender-fluidity genital mutilation — are superior to the ethics of 2004, way on back in the olden times when Bill Clinton and Barack Obama believed marriage was between one man and one woman, when Berkeley liberals championed free speech, and when the genital mutilation of minors was considered child abuse. Obviously, that hidebound thinking is now in our ethical rearview mirror. We know better.

Modern is not a synonym for contemporary. Contemporary means now, or about right now. Modern can have a more specialized meaning. It can refer to a way of thinking developing late in the 19th and early in the 20th century, suggesting that every generation or two presents its own unique problems different from all those before. Therefore, it must embrace and advocate different standards.

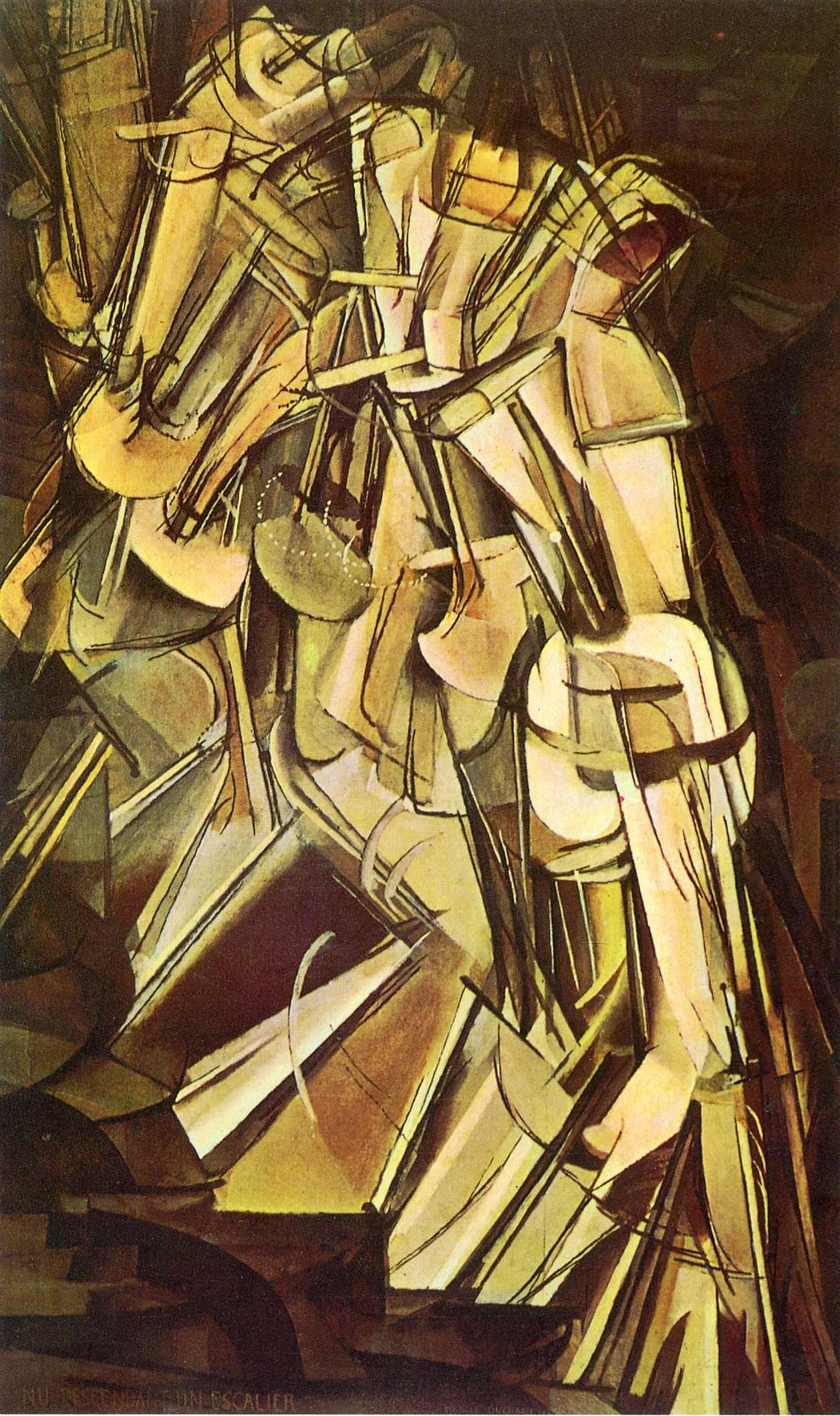

Modernism began in the field of art, particularly with Impressionism, holding that the older standards of art as essentially representation of or conformity to the external world must give way to (say) Picasso’s and Duchamp’s cubism. Here’s the latter’s famous, Nude Descending the Staircase:

If you can’t quite make out the nude, that’s good, because a Christian publication like mine shouldn’t be depicting nudes, but the point is that you wouldn’t have seen a painting like this anywhere in Europe before the 20th century. The artistic modernists were intentionally breaking free from all that went before to create an unprecedented painting that met the unique aims and objectives of the early 20th century. This means they couldn’t be bound by rules and standards of their predecessors.

The most dangerous modernism was theological modernism, sometimes called liberalism, which held that the unique situation of the early 20th century in the culture’s increased prioritization of science meant that most of the Bible had to be thrown overboard, and orthodoxy and the creeds deemed relics of an age whose standards are no longer relevant. The Bible conflicts with modern science, so the premodern Bible is no longer authoritative.

An irony of modernism is that, if it’s true, every new generation needs new standards, and this in turn means even the early modern standards soon became obsolete. Modernism becomes postmodernism, which in fact is simply hypermodernism. What comes after postmodernism? What is post-postmodernism? Well, just the latest shiny version of modernism.

The modern snobs look down on previous ages’ standards: “My great-grandfather and -grandmother should’ve gotten a divorce, but marriage rules were so constricting in those days.” “Can you believe the early American West where families routinely had 8 to 12 children?” “Without contraception or abortion, we couldn’t have a luxurious life.” “50 years ago the founding pastor of our church even preached against premarital sex. Everybody today knows that should be a non-issue.” And so on.

The possibility that the standards of the past might be superior to those of the present is simply not a viable option.

Traditionalist Snobbery

But modernists aren’t the only snobs. If the modernist absolutizes the present age, the traditionalist absolutizes a particular previous age. Modernist snobbery is the propensity of the Left, and traditionalist snobbery tends to be the propensity of the Right. It might be the Bronze Age Pervert, who absolutes the ancient pagan world and wants to reinstall it today. Or it could be Integralist Roman Catholics, who wish to reinstate, at least a degree, the church-state union of the medieval world. Or it could be ressourcement Protestants, who want to privilege the 18th century like Stephen Wolfe’s and other iterations of Christian Nationalism. Or it could be the Eastern Orthodox, who long for the undivided ecumenical church of the first four centuries. Or it could be Southern revival conservatives, who have convinced themselves that the Civil War was about states’ rights and only tangentially about slavery. Etc.

The problem with traditional snobbery is not its appreciation of tradition. Tradition of some sort is inescapable, and it should always be considered and appreciated to some degree. We must in some sense set tradition in opposition to the modernists’ incessant reinvention program.

However, the alternative to modernism is not traditionalism. It is a return, not to the past as such, but to the Bible. If you think about it, the traditionalists of Jesus’ day were the Pharisees. He was attempting to revive a very old Faith indeed, but he looked to many as the champion of a new Faith, because he broke so decisively with the dominant surrounding — and erring — traditionalist faith. It is also good to remember John Frame’s observation that traditionalist errors are often more dangerous than modern errors since traditionalist errors parade under the halo of respectable antiquity: if it’s old, it must be right. But sin is very old indeed.

Traditionalist snobs often specialize in knowledge of a particular historical era and patronize all who don’t share their specialized knowledge. They rightly scorn many aspects of modernity, but they seem blissfully ignorant of the obvious errors of the era to which they are so slavishly wedded.

(cont. below)

I’m sometimes asked the best place in the Bible to start for proving postmillennialism. I reply, “Genesis 1:1.” An optimistic eschatology rests in an optimistic protology. The sovereign Creator fashioned a very good creation that will fulfill his kingdom-expanding dominion purposes in time and history.

This primer shows what an optimistic eschatology looks like.

Get the book here.

(cont.)

Generational Snobbery

A third category of snobbery is generational snobbery. It pertains not to a contrast between different times in history, but, rather, between different times in the human life.

Older Generational Snobbery

Almost always it is reflected in Mike and the Mechanics’ famous pop song “The Living Years”:

So we open up a quarrel

Between the present and the past

An older generation is inclined to look with condescension and even contempt on the young adults of the time. The complaint seems not to have changed: “In our day, kid, we walked three miles uphill barefoot in the snow to school and three miles uphill home.” The youth are ungrateful, thoughtless, irresponsible, lazy, wasteful, profligate, and so on.

In fact, some of these descriptions are true some of the time. Unfortunately, they usually become generational over-generalizations. There are always plenty of exceptions, and certain youth at any time in history are morally superior, not only to the youth of the older generation when they were young, but even to that older generation living right now.

So older generational snobs gradually cut themselves off from assisting in conveying their wisdom to a younger generation that will succeed them — and listening to their challenges and aspirations. There’s not often recognition of a simple human fact: people change as they grow. Ignorant, intemperate young men or women often become knowledgeable, temperate older men or women.

Youthful Generational Snobbery

Of course, the generational chronological snobbery can come from youth also. It is generally more unseemly coming from youth (though no less mistaken), because there are few persons more unattractive than arrogant young people. We might grudgingly endure arrogant age, but arrogant youth are insufferable.

Youthful snobbery is ordinarily reflected in the assumption that their time or their cause has come. Life has passed the middle aged and the elderly by. The world as it is now was made for them. “This is our time.” This was precisely the attitude of Mao and other glittering-eyed young Marxists early in 20th century China.

Today this snobbery is pervasive among the youthful Leftists who occupy Ivy League campus buildings to promote Hamas murderers and who hate Jews, and equally by the New Right (including the Young Reformed Right), who are convinced they must capture the reins of political power to finally set society right, so help them God!

It is embarrassing to watch, an ineffectual slow-motion train wreck, but there’s really nothing new about it. At its base is not a political or philosophical or theological viewpoint, but rather a psychological and sociological mindset. Theology and philosophy are the variables. The psychology and sociology are the constants — they are the same generation after generation.

There’s generally more hope for the young snobs than the older snobs. The youthful snobs have time to be “mugged by reality” and come to their senses in middle age. But the aged snobs are concretized in their snobbery. Only the work of the Holy Spirit can alter this unattractive trait in both the young and the old.

Conclusion

But we need not passively wait until the Holy Spirit works. We must make the conscious attempt again and again not to lazily default to privileging our age or an earlier age or our period of life. We must intentionally carry on a dialogue between our time and previous times, and between those a generation older (even if they have died), and the generation younger than us (even if they are not yet born). Few have stated the truth as eloquently as Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy in the final pages of The Christian Future:

Historical man is taught by others, and rules others; and in these relations, he is compelled to realize himself. “He,” never exists, but is always between two times, two ages, as son and father, layman and expert, the end of one era, and the beginning of another. In their despair, the mental monadists [seeing from only a limited perspective] — who look for the mind inside the individual — call our time a period of transition. Sheer nonsense; the essence of time is transition. In so far as we speak or act, we can act or speak meaningfully only between two other generations, preceding and succeeding us, because we always come too late for ourselves….

The young depend on the choices made for them by their elders. An heir is not somebody who can choose what he should inherit; if he could make his choice, he would be self-made. But, in so far as his inheritance is determined, he is an heir, and under the laws of heredity. And to his heredity a man may say either yes or no, but he is caught in this one alternative which is not creative. He does, however, determine the background of the next generation.

Every historical time period partakes of the preceding one just as it does of the following one, which it helps shape. Every man is partly the product of his parents (or parental surrogates), just as he is the shaper of his children (or their surrogates). Because we are shaped by the time and people who preceded us, our insights happened before we could shape our lives by them. Thus, we always come too late for ourselves. We can only pray that our insights find root in our successors.

These truths show how vital it is to carry on a continuous dialogue between both the historical eras and the generations in a single lifetime.

In that dialogue, there is no room for chronological snobbery.

Yours for the cosmic Lord,

Founder & President, Center for Cultural Leadership

Isa. 49:1–2

Worldview Youth Academy in Tennessee

Friends, I hope you’ll join me this summer in Tennessee for this worldview event. Also, please consider sponsoring high school students for this transformational time.

Explore here.

Every Square Inch Symposium

I hope to see many of you at this exciting and informative event hosted by our friends at truthXchange:

Register here.

More great stuff

The Center for Cultural Leadership site is here.

My Amazon author page (print and digital) is here.

My I-Tunes sermons, lectures and podcasts are here.

You can find my sermons and lectures at my YouTube channel.

Sign up to get my blog updates here.

Here’s my Twitter feed.

If you want to get the free exclusive hard copy publication Christian Culture, please send me a Facebook private message.

The CCL phone number is 831-420-7230.

The mailing address is:

Center for Cultural Leadership

P. O. Box 100

Coulterville, CA 95311