Dear friends and supporters:

This week between Christmas and New Year’s has been more hectic than usual, so this e-newsletter will be shorter than usual.

An Omnivorous Reader’s Admission

I keep a fairly detailed record of the books I’ve read and intend to read, and I update this record every year’s end. As I planned that task, I pondered my reading choices and thought my approach could possibly benefit my readers.

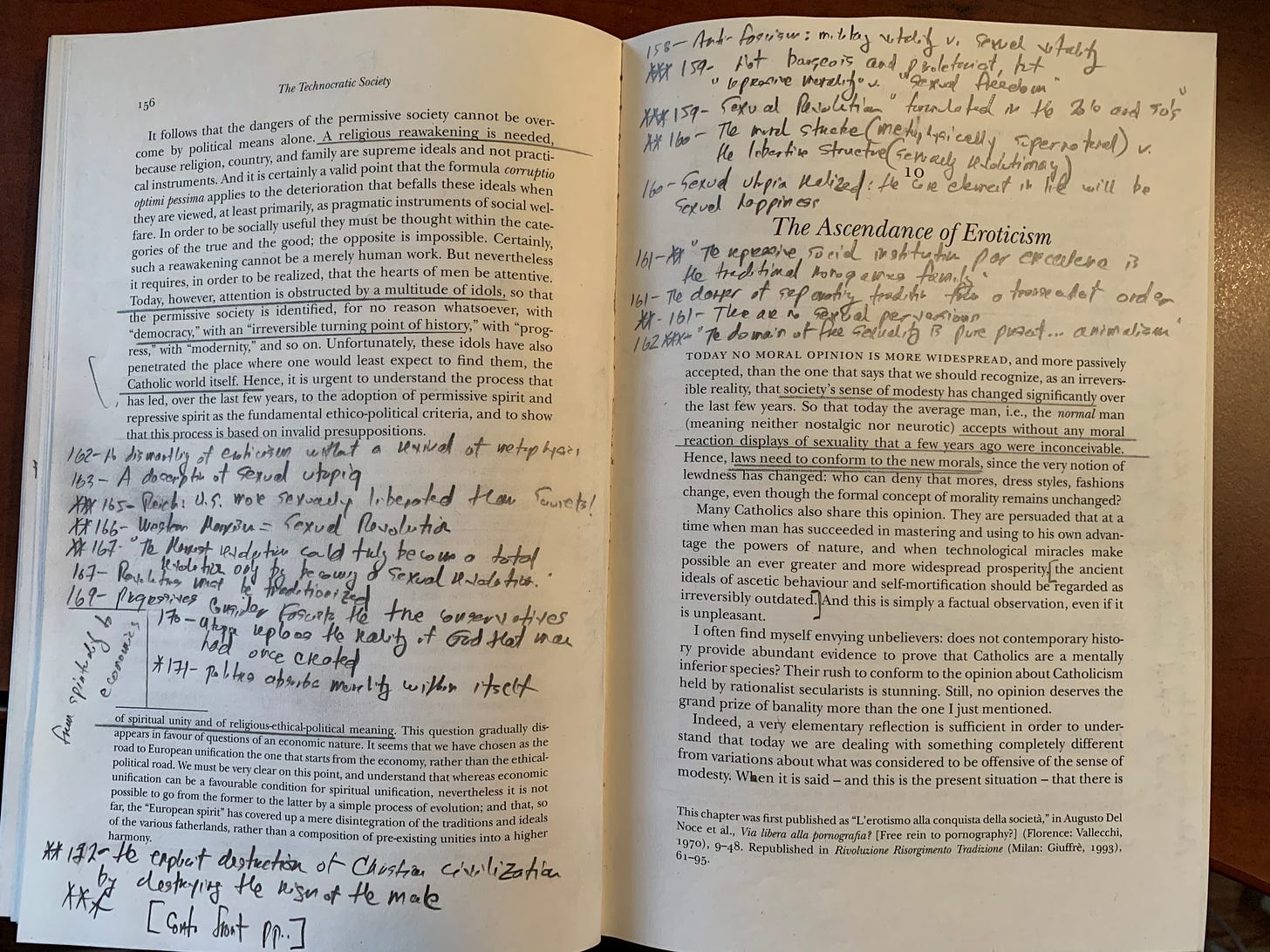

Because I’m an intellectual (cultural theologian), some well-meaning people describe me as “brilliant.” This is always an embarrassment, because I do know brilliant people, and I’m not one of them. I’m not exceedingly bright, but I am exceeding well-read. This annotation from a recent book (The Crisis of Modernity, by Augusto Del Noce) is typical, and shows how serious I am about reading.

The Modernist Reading Bent

I have increasingly retreated from prioritizing new books, not because they are less useful (I’m an author myself, and I sure hope a few people read my books!), but because in new books I tend not to encounter an alien historical atmosphere by which to judge unexamined assumptions of our present historical atmosphere.

In “We Are the Destroyers,” I noted the tenet of the late 19th and early 20th century movement known as Modernism that survives to this day and is expressed in Ezra Pound’s aphorism, “Make it new!” Kenneth Minogue summarized modernism’s dictum as “Whatever comes later is better.”

Unfortunately, this approach seduces many conservative Christians, who are conservative in their attitude toward books but not in choosing which books they’ll read. They somehow think that in books, “[w]hatever comes later is better.”

This is simply wrong. We sometimes state that a book written in 1950 (or 1905) is “dated,” and thereby of less value. But the fact is, all books are dated; they simply are dated in different ways. A brand spanking new book is dated by its appearance at the latest date. This can be as much a liability as an asset.

Lewis on reading

C. S. Lewis expressed this truism in a famous introduction drafted for a new translation of Athanasius’ “On the Incarnation.” In “On the Reading of Old Books,” Lewis stated:

We may be sure that the characteristic blindness of the twentieth century — the blindness about which posterity will ask, “But how could they have thought that?” — lies where we have never suspected it, and concerns something about which there is untroubled agreement between Hitler and President Roosevelt or between Mr. H. G. Wells and Karl Barth. None of us can fully escape this blindness, but we shall certainly increase it, and weaken our guard against it, if we read only modern books. Where they are true they will give us truths which we half knew already. Where they are false they will aggravate the error with which we are already dangerously ill.

The only palliative is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books. Not, of course, that there is any magic about the past. People were no cleverer then than they are now; they made as many mistakes as we. But not the same mistakes. They will not flatter us in the errors we are already committing; and their own errors, being now open and palpable, will not endanger us. Two heads are better than one, not because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the same direction [emphasis supplied]. To be sure, the books of the future would be just as good a corrective as the books of the past, but unfortunately we cannot get at them.

An example

Knowledgeable Christians tend to be aware of the disadvantage of reading premodern books. Let’s take an aspect of theology. The discipline of biblical exegesis (finding out what the Bible’s statements meant when written) has greatly advanced since the 19th century. A valuable development in Old Testament studies has been the discovery of the similarity between the suzerain (political) treaties of the ancient Near East and the structure of the Bible. The leading orthodox researcher in this field was Meredith Kline (see his The Structure of Biblical Authority). Not even the best premodern interpreter or theologian knew this relationship, because it hadn’t been discovered. We can better interpret the Old Testament today because of this modern discovery.

Because of our modernist outlook (no matter how anti-modern our theology), we’re less inclined to see the advantages of premodern interpretation. For one thing, it predated higher biblical criticism (HBC: the idea that the Bible should be interpreted as any other book) and, therefore, didn’t infect premodern interpreters. Matthew Henry’s commentaries betray not a whiff of the operational anti-supernaturalism of HBC, not because he manfully resisted it, but because there was none around to manfully resist.

Today even many of the more conservative biblical exegetes must constantly stave off the nagging doubts of HBC and occasionally reflect its malign influences. By contrast, while Matthew Henry’s exegesis lacks the benefits modern scientific exegesis, it also lacks the blight of HBC. Moderns condescendingly refer to premodern exegesis like Henry’s as “naive.” Another word for it is “believing.” I’ll let you choose whether you’d prefer (if you must have only one) naive believing premodern exegesis, or informed doubting modern exegesis.

Advantages of Development

This doesn’t mean we should want to turn back the theological and exegetical clock. Just as the Trinitarianism of the Nicene and post-Nicene Fathers (A. D. 325–415) is more advanced than that of the Apostolic Fathers (A. D. 80–180) since heresy after the era of the latter forced the former to investigate and clarify the Bible’s teaching, so faithful developments in the modern world help us to grapple with unfaithful developments in the modern world. Modern truth-telling writers help refute modern deceit-peddling writers.

An example

In my view, it’s possible that no Christian thinker before Abraham Kuyper (or maybe his less well-known predecessor Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer) understood the fatal damage that the Enlightenment inflicted on the Christianity of the 18th century. Even the most orthodox Christians of the time believed that reason was neutral and that Christians could best Enlightenment anti-Christian at their own rational game. Kuyper came to understand that reason was the servant of man’s spiritual condition, and that it was at this level that the battle with anti-Christian Enlightenment must be fought. Reformer John Calvin had a basic understanding of the fallenness of man’s reason, but he didn’t understand the full implications of that fallenness because there was no reason-deifying Enlightenment to force him to think that way. It’s not that Kuyper was a better theologian than Calvin, only that he was forced to address issues Calvin wasn’t.

In the same way, John Frame’s evenhanded analysis of contemporary worship music, and Millard Erickson’s refutation of evangelical postmodernism, could not have appeared in 1970. And it’s also imperative to realize, as I hinted above, it’s possible (and necessary) for modern books to champion premodern truth. A prime instance in the case of HBC is Gerhard Maier’s The End of the Historical-Critical Method.

Reading older books often won’t furnish the most effective conceptual tools for combatting false ideas that followed the era in which they were written. This, in fact, is one of the main reasons (not the the only reason) for writing new books on theology in the first place.

Speaking of which: here’s a new e-book you might want to acquire:

Conclusion

But while premodern and other older books can’t offer specific help with developments that occurred after they were written, they most certainly can help show us how many of those same (and other) developments have affected our thinking without our knowing it. They won’t flatter us in our naive modern assumptions.

If we let him, Matthew Henry will unintentionally critique our modern secularized Bible reading, to look at it as anything other than the very inspired and infallible breath of God.

John Calvin won’t give us an inch in our temptations to modern sexual autonomy, to the lifestyle dictum of even some professed Christians: my body, my choice.

And the modern theologian John Frame won’t allow us the luxury of chronological snobbery, either modernist snobbery (“Whatever comes later is better.” ), or traditionalist snobbery (“Whatever comes earlier is better.”).

We can help avoid both poles of chronological snobberies by following C. S. Lewis’ advice: “It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between.” In this way, you’re getting the advantage both of (1) highly developed historical ideas, as well as (2) less developed historical ideas that haven’t fallen prey to the bad instances of (1).

In my experience, it’s not important to be widely read only topically; we also should be widely read historically: knowing not just a lot about a lot of topics, but a lot about a lot of topics as they were understood in different historical eras.

So for 2021 why not compile a list of Good Old Books to read. You’ll be surprised to learn things that no recent book could’ve taught you.

Will you consider a tax-deductible donation to CCL via PayPal or Venmo? Or mail a check to CCL, Box 100, Coulterville, CA 95311. God uses you to keep us going — and expanding.

Personal

God blessed us this Christmas with a visit from our son David and daughter-in-law Rebecca from NYC. They had to leave for Rebecca’s parents’ house on Dec. 23, so we celebrated Christmas the previous weekend. We have so many children scattered around North America that a few years ago when they all arrived at different times, we celebrated six Christmases! It was such a blessing to have our four grandchildren with us overnight. Our son Richard and wife Samantha live in Vancouver, B. C. and thus couldn’t visit since the border is still closed. Our second son Ben lives in western Pennsylvania but works for FedEx and couldn’t visit since this is the busiest time of year for his company. Sharon and I sometimes wonder whether we’ll ever again have all of our children under a single roof simultaneously. But we treasure such great memories of them.

Next week’s scheduled title is “Gospel or Salvation?”

Thanks heaps to all of you who sent a year-end gift. And of course to all who faithfully support throughout the year, I am so indebted to each of you.

I pray that God rains down his blessings on each of you in 2021. Live, at all times, in hope and victory.

Yours for the King,

Founder & President

Center for Cultural Leadership

Prayer and Faith in a Time of Covid and Compromise

In this TruthXchange podcast with Joshua Gielow, I address the abysmal failure of many churches in the face of draconian lockdown orders, the tragic fear in which many Christians are living, the great power of answered prayer, and the eschatological victory in which we should actually be living.

Josh is a superb interviewer, and he elicited a couple of passionate mini-sermons from me.

More great stuff:

The Center for Cultural Leadership site is here.

My Amazon author page (print and digital) is here.

You can find my sermons and lectures at my YouTube channel.

Sign up to get my blog updates here.

Here’s my Twitter feed.

Here’s my Parler feed.

If you want to get the free exclusive hard copy publication Christian Culture, please send me a Facebook private message.

The CCL phone number is 831-420-7230.

The mailing address is:

Center for Cultural Leadership

P.O Box 100

Coulterville, CA 95311