Post-Liberal is Post-Christian

A Christian state is not a state that imposes Christianity, but one that creates a framework for liberty. The Christian state is the minimal state.

Dear friends and supporters:

Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address declares that the United States were “conceived in Liberty,” but liberty is not a key theme for many Americans these days. Leftists and their chief institutional vehicle the Democratic Party loudly clamor for equality and its recent highfalutin variation, “equity.” They seem to prefer the word “freedom” to liberty, but the freedom they envision is not freedom as understood historically by most Americans, and certainly not by the U.S. Founders.

Freedom From

The Founders understood freedom as freedom from undue political and other communities’ interference. Freedom meant that you are free to live your life according to the dictates of your conscience within the broad structure of the moral order, meaning God’s order, including biblical law or natural law.

Freedom meant that the state cannot determine the kind of life you must live, the religion you embrace, the aspirations you hold, whether or how you will rear a family, what you will do with your property, and so forth. Freedom meant that while family and church are vitally important, they (and not merely the state) may not coerce your conscience, your choices, and your kind of life. You are not bound by a caste as in India and, to a lesser extent, England, to continue in the station in which you were born; you’re free to change, to advance yourself.

This is individual liberty, liberty from intrusive communities, especially the only coercive one, the state. This view might be accurately described as freedom from.

Freedom To

Leftists, on the other hand, since the French Revolution, have stressed freedom to.1 All humans are entitled to a particular standard of living, to being treated in a certain way, to a particular relationship with their fellow citizens, and a major goal of politics is to guarantee that status. To put it another way: we are not truly free unless we can enjoy a particular kind of life. You shouldn’t be merely free to pursue your happiness. The state must guarantee that other people make sure you’re happy.

Conservatives would argue that you are free if you can enjoy your life unmolested by coercive external forces, chief of which is the state, that is, freedom from (most) external political constraint.

But for Leftists, the life of freedom is one of equality with and acceptance and approval by others. This means that I am not truly free unless I have a basic material standard of living, unless my lifestyle is accepted and approved by my fellow citizens, and unless I am immune to the non-coercive rules of social institutions (“civil society”) like the family and church (they may not discriminate against me for being irresponsible, gay, Marxist, or transgender; if they do, I’m no longer free).

What Leftists consider liberty or freedom, the U.S. Founders and conservatives (until lately) consider oppression: coercion by the state.

What conservatives consider liberty (freedom from statist coercion), Leftists consider oppression, since that very freedom from state oppression permits significant human inequalities in wealth, accomplishment, acceptance, and approval. Conservatives want equality of processes; Leftists want equality of outcomes. These two are diametrically opposed.

The New Anti-Liberty Conservatives

An unexpected development in the last few years has been the conservatives’ abandonment of the priority of political liberty (freedom from), the very people that have kept it alive in the throes of modern Leftism, and an embrace of freedom to.

This anti-liberty (sometimes more benignly labeled “illiberal”) message tends to come in two forms.

Integralism

The first is Integralism. This is the illiberalism of many anti-liberty Roman Catholics. They wish to restore something of the medieval unity of church and state. It wouldn’t be fair to criticize them for wanting simply to reproduce the church-state arrangement of the medieval world. However, they believe that the separation of church and state as divided spheres under God’s authority (the view of the U. S. Founders) has eventually led to today’s secularization, and they want to restore a Christian basis for society by restoring, if not an ecclesiocracy (the rule of the church in society), at least a greater role for the church (their church, of course) in framing the unified political society, especially national politics (the long-time U. S. conservative tenet of states’ rights isn’t on their radar).

Illiberalism

Then there are Protestant or non-Christian illiberals, sometimes simply called post-liberals. They don’t want to restore a union of church and state. Rather, they want the state to take a more active role in nourishing and in some cases even imposing a conservative or virtuous (even Christian) vision in society.

Like the Integralists, they believe the free society envisioned by the Founders, sometimes called classical liberalism (see “Two Liberalisms, Two Anti-Liberalisms”), has provided the liberty for secular antinomians and hedonists to dominate society and threaten those very founding freedoms. If you grant freedom, some people just always seem to abuse it.

Therefore, the answer is to use “any means necessary,” and notably the coercive power of the state (“Why should the Cultural Marxists be the only ones who get to take away people’s liberty?”) to oppose this antinomian cultural vision and impose a more virtuous version.

This means, of course, curtailing, at least temporarily, the free society, which the illiberals claim has failed. Why widespread political liberty was compatible with a basic virtuous consensus for 200 years but suddenly now is not, they never seem to explain.

Differences between the Integralists and the non-Roman Catholic or non-Christian postliberals, and even differences within each group, don’t negate what both hold in common — the idea that the state exists not simply as a framework to protect liberty (the Founders’ Protestant-inspired view), but as a vehicle to promote the “common good,” however that is defined.

The Conservative-Leftist Agreement

On this point, the Integralists and the postliberals stand with the Leftists. The only disagreement is over how to define the “common good.” For Leftists, it is “equity,” “social justice,” antiracism, and shared economic resources. For the illiberals, it is the Christian Faith, the traditional family, and (sometimes) a national(ist) culture.

Both, however, envision a more activist role for the state. In fact, we could say that both are statist. What both have willingly and intentionally abandoned is liberty as the essential feature of the political aspect of society.

Liberty for illiberals is merely a second-order benefit of a particular kind of society. The state forges a people sharing a unified vision (a “common good”), and then politicians dole out liberty.

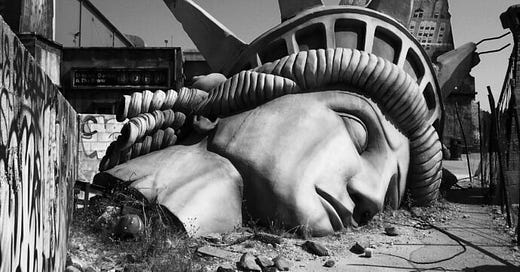

Liberty is a consequence, not a cause, of a unified national purpose. (This, by the way, is just what Lenin and Mussolini and Hitler and Pol Pot believed.)

Forever Fusionist

This illiberalism of both Leftists and conservatives stands in opposition to the U.S. Founding philosophy and, more importantly, to the generic Protestant Christianity that molded it.

One noted 20th century conservative burdened to show that virtue and liberty are equally important politically was Frank S. Meyer,2 a colleague of William F. Buckley’s at National Review, and he invented the political nomenclature “fusionism” to describe this viewpoint. He meant that a free, generically Protestant society3 fused liberty and virtue, never one without the other.

Meyer was an unflagging champion of individual liberty versus national collectivism. He believed, with the Founders, that governments are instituted among men to protect life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and that there’s no other justification for civil government.

Meyer argued against the collectivism of both Left and Right, which held that individual liberty is a consequence of “the good society.” Meyer taught that individual liberty is necessary to create a good society. Liberty comes first. There’s no good society apart from individual liberty. Or so consistent Protestantism teaches, and so the U.S. Founders believed.

Protestants, starting with Luther, stressed the inviolable individual conscience before God. Classical liberalism is a political application of Protestant theology; and its 18th century Enlightenment champions, even if not formally Christian, were influenced by their Protestant predecessors to stress political individualism, though (of course) not the radical individual autonomy of today, which would have horrified them.

This doesn’t mean all Protestant societies have been classically liberal. No one would mistake Calvin’s Geneva for a free society. But Protestantism’s basic theological tenets tend to produce — and in fact have produced — free societies, all over northern Europe and North America. And as Protestantism has faded, so has political liberty.

Virtue Requires Liberty, and Liberty Requires Virtue

Meyer did not believe that freedom is an end in itself, but he was confident there can be no virtuous ends without it.

I myself would put it this way: man’s chief task in the earth, the cultural mandate (Genesis 1:28–30), presupposes political liberty. You need a lot of political liberty in order to obey Genesis 1:28–30. Statism prohibits the most virtuous actions.

Meyer believed that the right anthropology (view of man) necessitates a political philosophy, classical liberalism, in which the role of the state is to suppress certain externally evil acts, not to inculcate virtue. In the language and intent of Romans 13, the civil magistrate rewards the obedient by punishing externally injurious evildoers, not by forging the virtuous society, even a Christian society.

That’s not the job of politicians. That’s other people’s job.

Alternatively, both Integralists and postliberals are interested in a coercively imposed, nationalized, virtue. That’s all fine and dandy as long as it’s your common good that’s being coercively imposed.

But as Robert Sirico, a classically liberal conservative Roman Catholic, famously reminded fellow Catholic but Integralist Rusty Reno when Reno advocated statist action to impose virtue: “You won’t be on those committees.”

Liberty Is the Chief Political Common Good

The U.S. Founders, influenced by Protestant Christianity, recognized that the common good secured by politics should be liberty, while the cultivation of common good as the Christian Faith and virtue should be the role of what we today call civil society, or mediating institutions like the family and church and, most of all, the virtuous individual. Kim R. Holmes puts it this way:

Like the founders, they [traditional conservatives] look to the social cohesiveness and discipline by religion and morality in civil society to restrain the potential extremes of political liberty that are always a risk in a free society. It is certainly true that the balance between liberty and order has broken down in America. But the answer advanced by traditional conservatives is not to throttle freedom or individual rights by government, but to rebuild the broken structures and institutions of civil society and religion that once limited the extremes of liberalism, but which are today in some cases their primary enablers.4

Meyer, who was not a Christian at the time he wrote his book, nonetheless recognized that classical liberalism of the free society is a gift of Christianity. In other words, fusionism is a distinctly Christian political philosophy. A collectivist, illiberal political philosophy, whether Left or Right, is not Christian.

Society does not become more Christian because its politicians impose Christianity. Imposed Christianity is not Christianity. Christians can support the free society precisely because we believe in the power of the Spirit, and not in the power of the state. Islamists enforce religious tenets by the power of the sword, but we Christians believe in the power of the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God (Ephesians 6:17). Christians shouldn’t ape Islamic political philosophies.

Conclusion

Nevertheless, it’s understandable that so many Christians committed to Christianizing culture are buying into illiberalism. They recognize the depravity of our society, and they rightly understand that Christianity is the only cure.

They fail to recognize that a politically imposed Christianity is not a cure, but would only contribute to the disease. Statism, even — perhaps especially — a statism motivated by a desire to coerce virtue, is as bad as the disease. Statism is just another form of depravity.

The new conservative post-liberals are justifiably disturbed by all of the Leftist cultural victories — same-sex “marriage,” transgenderism, cancel culture, white supremacy nomenclature — and they’re panicking into giving up the hard-won gains of the Protestant free society by angling to capture coercive politics to impose their cultural vision.

This is the naïve, lazy man’s way. Leftists gained hegemony because Christians and other conservatives long refused to play the long cultural game. We lost our culture over the last hundred years, and we won’t regain it over the next ten years. We should work gradually to recapture institutions and, where that’s not possible, to create alternative institutions, and, if we succeed, eventually we’ll foster a radically decentralized politics. If you capture the culture, you tend to get politics thrown in for good measure.

But you can capture politics every election and still lose the culture. In fact, in partial measure, that’s precisely what’s been happening to conservatives over the last 40 years: political victories coinciding with cultural defeats. Drag queen story hour wasn’t imposed by Barack Obama or abolished by Donald Trump. You must win cultural battles on cultural battlefields.

What a Christian State Really Means

As Christians, we are called to bring every area of life and thought under the authority of Jesus Christ in his word. In politics, that means a radically reduced state, chained to its biblical limits. In a sense it is Christian Libertarianism, though far from an Ayn Rand sort.

A Christian state is not a state that imposes Christianity, but one that creates a framework for the liberty of Christians and others to live according to their conscience under God’s providence. The Christian state is the minimal state.

The Christian stake in today’s chaotic politics, therefore, is to get the state out of the “common good” business or, rather, to recognize that liberty is the chief Christian common good the state is to guarantee. It’s not the only common good, but none of the rest (like justice) can exist without it.

Then individuals and families and churches and the rest of pre-and non-political civil society will be free to spread Christianity in society (not to impose it in politics) and to bring all things gradually under the authority of Christ the King, who is the King of virtue and liberty, for where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty (2 Corinthians 3:17).

So while many sincere Christians are numbered among the illiberals, illiberalism itself is not consistently Christian. For these reasons (and others) my colleague Dr. Brian G. Mattson and I are proud members (along with the great Dutch thinker and politician Abraham Kuyper) of what Brian terms Team Liberty.

I therefore urge you to resist the siren song of seductive statism at the root of the illiberal program, whether of the Left or Right.

Will you consider a tax-deductible donation to CCL via PayPal or Venmo? Or mail a check to CCL, Box 100, Coulterville, CA 95311. God uses you to keep us going — and expanding.

Personal

I’m finally finishing Creational Marriage: Issues and Controversies, set to coincide with my and Sharon’s 40th wedding anniversary. I hope it’s out in November. It’ll deal with such topics as egalitarianism, singleness, LGBTQIA+, same-sex attraction, aborticide, eros, the child-free life and many other controversial topics.

If you haven’t subscribed to my DocSandlin blog, or my iTunes audio and YouTube channels, please consider doing that today.

On Sunday, October 9 I’ll be preaching for my dear friend David Shay at Living Church International in western Pennsylvania. Sharon and I to hope see some of you friends there.

On Wednesday, October 26, I’ll be preaching in chapel at Providence Christian College, a top-notch, distinctly Reformational school in Pasadena, California.

On October 28 I’m addressing “Christian Culture and Biblical Law” for my friends at the annual ReformCon 2022 event in Mesa, Arizona (sponsored by Apologia, Pastor Jeff Durbin).

The week before Thanksgiving Sharon and I will be traveling to Mexico where I’ll be lecturing to a church leaders’ conference outside Mexico City.

Next week I hope to write “Classical Liberalism, Simply Explained.”

If you believe in liberty, please pray for and support CCL.

Yours for Team Liberty,

Founder & President, Center for Cultural Leadership

The Dialectical God, the Static God, and the Covenantal God

More great stuff:

The Center for Cultural Leadership site is here.

My Amazon author page (print and digital) is here.

My I-Tunes sermons, lectures and podcasts are here.

You can find my sermons and lectures at my YouTube channel.

Sign up to get my blog updates here.

Here’s my Twitter feed.

If you want to get the free exclusive hard copy publication Christian Culture, please send me a Facebook private message.

The CCL phone number is 831-420-7230.

The mailing address is:

Center for Cultural Leadership

P. O. Box 100

Coulterville, CA 95311

Isaiah Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” Four Essays on Liberty (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1969), 118–172.

Frank S. Meyer, In Defense of Freedom and Related Essays (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1996 edition).

Only one Roman Catholic, Charles Carroll, signed the Declaration of Independence.

Kim R. Holmes, “The Fallacies of the Common Good,” The New Criterion, Vol. 40, No. 5 [January 2022], 17, emphasis added.

Do you have examples of Christians who want to impose statism? I understand your points in theory, but to have concrete examples would be helpful.

I share your concern that would-be Christian nationalists are wise enough to understand that their project needs to be a minimalist state, e.g. Christian Libertarianism. On those grounds, I stand with you. They just don't get it yet.

But to offer constructive criticism, there really is nothing in the bible's depiction of the magistrate's proper duties which preclude coercion. 1st Peter 2:14, Romans 13. Coercion, it seems, is a command to the magistrate, not an option to be exercised by him should the people give a thumbs-up.

And I'd also point out that there is no such thing as neutral coercion. Polygamy is for heretical cults, but our political order has forbidden it on Christian grounds.

I appreciate your description of how biblical, dare I say, Christian, the US founding's theory was; with its antecedents in Luther and the reformation. I agree with you on that.

Therefore it will eventually be counterproductive to your project to claim that the power of the state must not "coerce Christianity" when you're making that pronouncement from a pedestal built upon Christianity which was encoded into civil law on Christian grounds. It's so Christian, in fact, that there were actually objectors to it when it happened. Dare I say, they were coerced.

I admit it's a painful conundrum we are in, and the last thing I want is a Christian political savior, raring to build walls on the border, send out our troops yet again to democratize the planet, or give money from the public purse in mercantilist projects to enrich lazy US businessmen.

We need to face the fact that Classical Liberalism, good as it has been, at the end of the day, is just another -ism. You can't build a theory of the magistrate's duties on it. You have to use the bible; Peter and Paul.

Blessings.