The Kingdom of God Is Not a Personal Salvation Cult

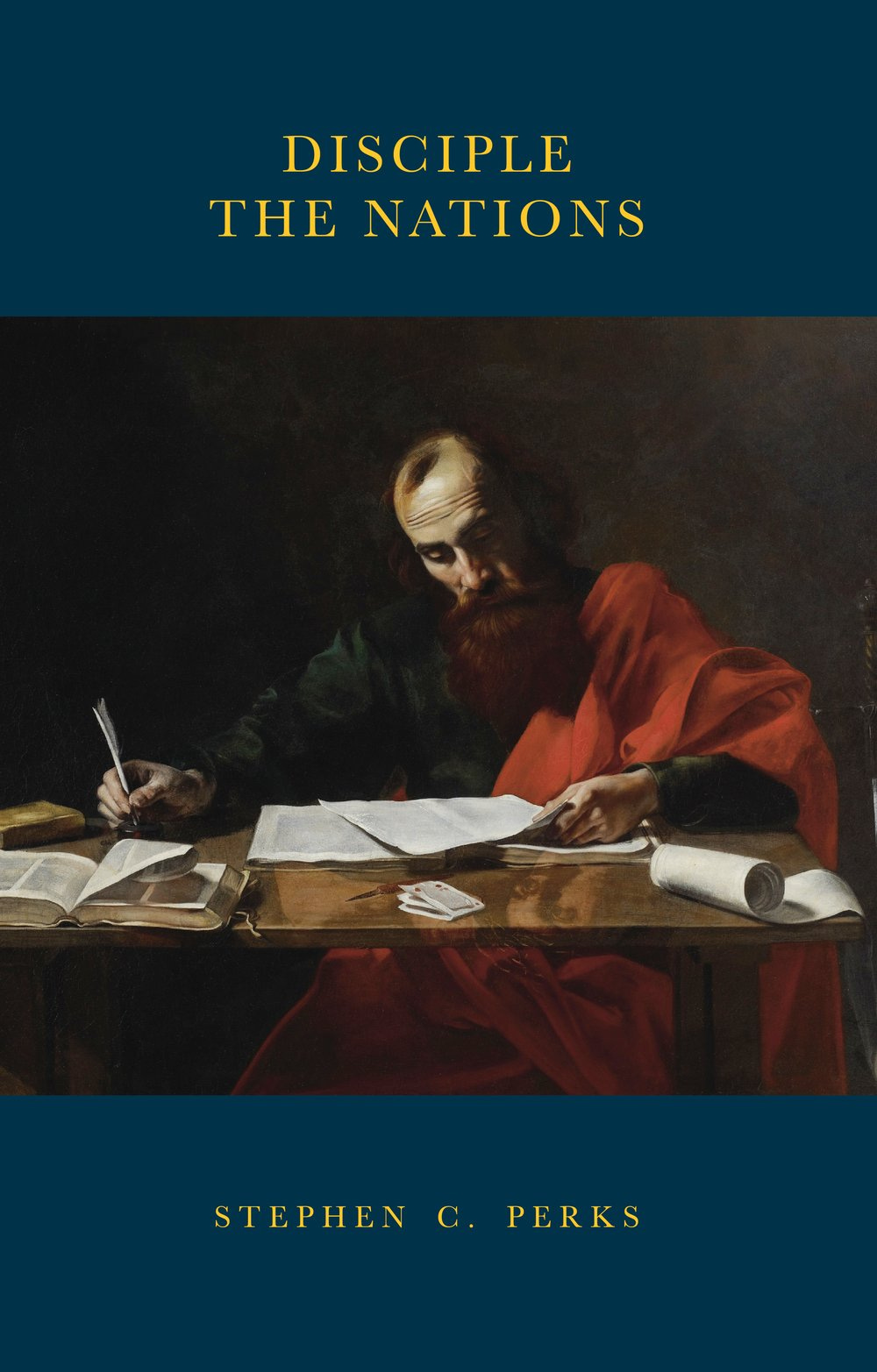

Stephen C. Perks’ latest iconoclastic essay bluntly dismisses Protestantism as a failure and offers a renaissance of the apostolic kingdom of God as the only viable replacement.

Dear friends and supporters:

One of the most interesting, intriguing Christian thinkers today is the reclusive British author Stephen C. Perks, Founder and Director of the Kuyper Foundation. His latest book, Disciple the Nations (hardcopy for sale as well as free downloadable PDF here), characteristically blunt, bold, and iconoclastic, argues that Christians throughout history have seriously undervalued the kingdom of God, severely misdefined the church, and fatally sabotaged biblical truth. Within the space of 80 pages, Stephen manages to summarize most of the themes addressed in his previous 11 books. In this review I use his Christian name, because Stephen has been a friend for about 30 years, beginning about the time he wrote his first book. I was once a member of his international staff of writers when the Kuyper Foundation published Calvinism Today and Christianity and Society. In Disciple the Nations, Stephen slays numerous sacred cows, and since CCL is committed to the Kuyper Foundation’s precise objective (“Promoting the Renaissance of Christian Culture”), this book is worthy of consideration, at least for me, and I hope for you too.

There Was Never a Reformation

We speak of the Protestant Reformation, charges Stephen, but if Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, Bucer, Knox and others were attempting to reform the Roman Catholic Church, they were miserable failures. All were either summarily expelled or voluntarily separated from the Roman communion. “What we call the Reformation was not a Reformation at all. It was an Exodus” (17). Hence, “[t]here never was a Reformation, there are no Reformed churches, and Reformed theology is a fiction” (17). It’s more correct to speak of the Protestant Renaissance, or even resurrection. God didn’t reform the medieval Latin church; he started something new. That was the Protestant Renaissance, what we today call (incorrectly) the Protestant Reformation.

Stephen is not merely making a descriptive observation. He’s also offering a prescriptive paradigm: when a movement or institution departs from the Faith, God almost always calls his people out and starts something new honoring him. With respect to Christian movements in history, God is generally a God of renaissance or resurrection, not reform or rejuvenation.

Stephen is not arguing for Anabaptist separatism or sectarianism. Christians should purify specific institutions if they can. But when movements hurtle wholesale into apostasy, they become irreformable.

Nor is Stephen is a sectarian Protestant. Rather, he’s an equal opportunity demolition tactician. Just as it was necessary for the “reformers” to jettison Rome, so it is necessary for Christians today to jettison Protestantism. It has become something so radically at variance with biblical truth, that it’s simply irreformable. How?

There Is No Church in the New Covenant Era

In misunderstanding the church, Christians have misunderstood what God is actually doing in the world. Almost all English New Testaments refer to the church, but there is no church in the New Testament era. “Church” almost always translates the Greek word ecclesia, but ecclesia does not mean “church.” Church basically means the Lord’s house, but ecclesia denotes (as originally used in Greek) a called-out community, specifically a political community in the ancient world that made decisions about the city-state. In identifying the ecclesia as a church, Christians have long reduced it to a building and to its public worship and, in particular, to its clergy and institutional trappings. There was a church in the old covenant era (the temple, the Lord’s house), but in the new covenant era the ecclesia usually met in homes. The new covenant is, properly speaking, unchurched. (Which doesn’t mean it’s anti-communal or individualistic.)

Of course, the Greek meaning of a biblical word is not of itself decisive. We must understand how a word is used in a context to grasp its meaning, and the Holy Spirit is free to vest words with new meanings.1 But Stephen draws attention to an interesting fact:

The word ecclesia is a political term not a cultic term; i.e. it is not a term denoting the meeting of a group of people united by their devotion to a particular deity and the maintenance and promotion of his cultus. There were many words available to denote such cultic groups in classical Greek culture and literature, which the authors of the New Testament could have used to identify the assembly of Christians, primarily as a cultic group devoted to the cult of Jesus. But the New Testament, written by men under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, does not use such words of the assemblies of Christians. (12, emphasis supplied)

According to Stephen, ecclesia denotes something quite different: the people of God as a political body pressing the kingdom of God (basileia) in the earth. By “political” he doesn’t mean modern statist politics; he means God’s earthly government. The ecclesia is the community of Christians called out by God to extend his government (kingdom) in the world. The Lord’s day worship presided over by Christian leaders is certainly an aspect of the ecclesia life, but that is not the meaning of ecclesia.

Tyndale correctly translated ecclesia as “congregation,” but there was a nearly ubiquitous subsequent attempt by establishment Protestant churchmen (and their “control cults,” 71) to reduce the community to public institutional worship controlled by clergymen. This is where “church” originated in our Bibles.

In this way, Protestantism almost from the beginning became dangerously blunted. The ecclesia was reduced to a church.

The Kingdom Generates the Ecclesia

The kingdom of God is a social order, and it generates the ecclesia whose objective is to contribute to the expansion of that order. This means creating an antithetical alternative to the secular and neopagan order presently engulfing the West, just as the first new covenant ecclesia gradually superseded the ancient pagan Roman order. The goal of God’s kingdom is to replace any contra-Christian order by the preaching of the gospel in its totality, and not the gospel as it has been reduced to a “personal salvation cult” (31) in the modern church. In privatizing the Faith and limiting it to its liturgical trappings, Christians have transmuted a robust biblical faith into modern “mystery cults” (23).

This sharply contrasts with new covenant-era Christianity, which was persecuted precisely because it championed the kingdom of God, and posited Jesus Christ as King of the world. Imperial Rome couldn’t care less if citizens practiced mystery cults, but it couldn’t tolerate anybody that publicly reverenced a lord superior to Cesar. This is precisely what the early Christians did. They weren’t revolutionaries by any means, but they refused to acknowledge Caesar as lord. The earliest ecclesia was a kingdom community, not a mystery cult. It put the kingdom first, just as the Lord had required:

Jesus never told us to plant Churches. He said he will build his ecclesia, his assembly. He told us to seek the Kingdom of God and his righteousness (i.e. justice, not piety) and in the Great Commission he gave us a command to disciple nations, not plant Churches. Assemblies of Christians are a consequence of the Great Commission not its goal. The goal is all nations embracing the kingdom of God and living according to the covenant. (22)

Stephen makes the poignant observation that for 2000 years Christians have reversed the roles: They’ve tried to do Jesus’ job of building the church (ecclesia), and they’ve refused to do their own job of putting the kingdom first.

Today’s Evangelicalism Preserves a Long Line of Heresy

One reason the “church” has failed to prioritize the kingdom is that it has reduced biblical authority to the New Testament. In this move it has broken decisively with Christian orthodoxy. Throughout church history, one trait that united the diverse heretical movements was their repudiation of the Old Testament. The Marcionites, the Manichees, the Bogomils, the Cathars and others saw the Old Testament as inferior and sub-Christian. The orthodox, by contrast, insisted on the unity of the biblical canon. This means many modern evangelicals have preserved the heretical medieval line of a truncated canon:

When did the New Testament replace the Old? Not in the apostolic age. Not in the sub-apostolic age. Not in mediaeval times. Not at the time of the Reformation. Not until the twentieth century — except among the heretics. Until the twentieth century, the rejection of the Old Testament, Moses and the law of God was a definitive feature of heresy. It still is. This is the age of heresy. This continues to be a highly relevant and problematic issue.

Throughout the two thousand year history of Christianity there have only been two groups of people that have rejected the Old Testament, Moses and the law of God: heretics and modern evangelicals. Or rather, I should perhaps really say, only one group of people: heretics. The modern apostate and heretical Church has led the world to ruin. (53)

It’s difficult to preserve biblical kingdom faith when you jettison two thirds of the Bible.

The Great Commission Does Not Command Us to Make Disciples

Just as Christians have misunderstood the church, we have also misunderstood the so-called great commission. It is often translated as something like “Go and make disciples of all nations.” In reality, Stephen argues, the Greek structure of the text in Matthew 28:18–20 demands, “Go and make all nations my disciples” (60–61). The difference in wording is slight while the difference in meaning is momentous. If we are to make disciples within all nations, that means Christians are called to win people to Christ and disciple them. That, of course, is an indispensable calling. But according to Stephen, that’s not what the great commission is specifically commanding. Rather, it’s commanding that the nations themselves be discipled. This means bringing entire nations under the authority of King Jesus, not merely winning individual disciples from within those nations to King Jesus.

Nations (ethnos) are not equal to what we today call nation-states, which were non-existent in the ancient world. In the Bible, “nations” refer to groupings of people bound together by habit, use, custom, cultic ordinance, and law (13). To disciple the nations, therefore, doesn’t mean to wrest political control (as we currently understand it) from the civil government in those nations, but, rather, to bring large, cohesive groupings of people under the authority of Jesus Christ by the gospel. This actually happened historically in a number of nations, and, Stephen observes, this is precisely what the great commission demands.

The Apostles Oversee the Ecclesia

This suggestion might get Stephen labeled a modern charismatic, but he’s not using the term apostle in the same way. In the Bible, apostle is a sent one, a missionary, in fact. Stephen postulates that the Bible never claimed that apostleship is limited to the original 12 apostles. The apostles are God’s messengers (like Paul) who declare and perpetuate the kingdom of God. These apostles are the foundation of the church. Stephen points out that apostles and prophets, and not pastors and teachers, are the church’s human foundation (Ephesians 1:18–20). A community of these apostles lays the groundwork for the ecclesia. That’s the way it happened in the original new covenant era, and this is the way it’s supposed to happen today. Paul’s (and the other apostles’) kingdom message naturally led to the formation of churches. This is very different from celebrity pastors for whom the church (their church) is the be-all-and-end-all, preserving a celebrity or personality cult.

It is these apostolic communities of kingdom missionaries that, like the new covenant apostolate, bring together individuals out of which today’s ecclesia (“church”) is formed. This apostolic kingdom community, not the ecclesia, comes first both logically and chronologically.

According to this paradigm, the kingdom has priority, and the ecclesia subsists to train Jesus’ kingdom people. The ecclesia is never an end in itself, but it’s designed to extend the kingdom of God:

Setting up Churches has not and will not provide this leadership. Instead we need to create new sodalities [guilds or brotherhoods], new centres of apostolic vision and mission, new communities committed and dedicated to the Kingdom of God as a counter-revolutionary prophetic social order governed by the covenant of grace that has come into this world now and is meant to grow until it displaces and eventually replaces the social orders of men. The assemblies of Christians are a result of this, not its cause, and as long as they follow the apostolic leadership they have an important role to play. If they reject the biblical model they will be blind guides leading the blind into the ditch, which is just what has happened. (78)

This is what it means to disciple the nations, and how God intends that it’s done. Because Christians have largely misunderstood this paradigm, they have generally, though not always, failed in their kingdom task. Our calling today is to mount a new Renaissance, leaving behind the failed, pitiful, inward-focused, incestuous Protestantism while returning to the biblical-apostolic kingdom vision.

Conclusion

What do I make of this proposal? In broad outline, I agree with it. Protestantism was a renaissance, and not a reformation. Christians are never bound to perpetuate movements, only to conform to God’s truth, and separate from apostate movements and start new ones.

The ecclesia is not a church. The kingdom, not even the ecclesia (which is vital), must be our priority. The kingdom generates the ecclesia.

Likewise, modern evangelicalism in many segments has perpetuated an older heretical tradition in its dismissal of the Old Testament. It is a jolting verdict, but it’s warranted.

The biblical Gospel is not a personal salvation cult. (See my “Gospel or Salvation?”), although, of course, individual salvation effectuated by our Lord’s sacrificial death and bodily resurrection is a central imperative of biblical faith.

I think Stephen is on more fragile exegetical and theological ground in proposing that the ecclesia in the post-biblical era is a consequence of the vision of an apostolic community, a godly kingdom elite that oversee the ecclesia. It seems to me the Bible enumerates a greater role for local pastors/shepherds/bishops; but to be fair, Stephen does not specifically deny this role. Whether and how the New Testament era apostolate operates today warrants greater attention.

In any case, the objective of the kingdom of God is to create a Christian social order, a Christian civilization, a Christian culture. This is what God is doing in the world, and this is what the cross and resurrection and reign of Christ are designed to accomplish. Personal salvation is a critical aspect of this objective, but by no means the full objective.

Although I might not have phrased his theses of Stephen has, and though I disagree with details here and there, he has offered a refreshingly biblical vision of the kingdom of God. It is imperative that we recover the broadest outlines of this vision if we expect the Lord’s kingdom to burgeon in our lifetime and later.

Will you consider a tax-deductible donation to CCL via PayPal or Venmo? Or mail a check to CCL, Box 100, Coulterville, CA 95311. God uses you to keep us going — and expanding.

Personal

Tomorrow our youngest son David, a faithful Christian young man, will arrive from New York City, where he teaches and works in the administration at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice (City University of New York). We get to see him less than we do our other children, so Sharon and I cherish this opportunity. We’ll miss our daughter-in-law Becky, who had to stay in Manhattan for work.

In about two weeks, we’re flying to Vancouver, B.C., where our older son Richard will be ordained to the diaconate (in preparation for full ministerial ordination). We’re privilege that he’s asked us to assist with his investiture.

In April we’re driving to central Minnesota for the Common Slaves Conference led by the bold, godly pastor Eric Anderson. The conference theme is “My Place in this World: What are the God-given purposes for the Christian today?” I’ll be speaking on “God’s Will for Your Life: You Can’t Improve on Creation,” “Extraordinary Christianity or the Ordinary Means of Grace?” and “Dare to Be a Daniel in Prayer.” My dear friend Ardel Caneday will join me.

The dates for the Runner Academy of the Ezra Institute are June 5–15 in spectacular Golden, B.C., adjacent to Glacier and Banff National Parks, and I’ll be lecturing numerous times. This high-level event is for Christians ages 19-39 seeking a deeper knowledge of Christian worldview within a profound ambiance of communal worship amid breathtaking scenery. Students will be staying in a spacious timber-framed lodge with incredible views of the Rocky Mountains.

Parents, grandparents, and church leaders: please consider sponsoring students for this once-in-a-lifetime, transformational event. Few investments in this life are more valuable than funding Christian young adults to grasp and incorporate a kingdom view, translating it into a kingdom lifetime.

And please continue to support CCL generously. I need you.

For the King and His Kingdom,

Center for Cultural Leadership

Anthony C. Thiselton, “Semantics and New Testament Interpretation,” New Testament Interpretation: Essays on Principles and Methods, I. Howard Marshall, ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1977), 75–104. Thiselton relies on James Barr’s classic The Semantics of Biblical Language.

I've been listening my way through this. So great!

Praise God! So good to see others elaborating on the difference between ecclesia and church:

"...When you hear the word “church,” what comes to mind? For most people, the word “church” means one of two things, depending upon the context:

1) A building they frequent once, twice, or three times a week in which to pray, sing praises, and listen to preaching.

2) The people who allegedly make up the church, aka the body of Christ, who frequent a building known as a church to do the things depicted in Option #1.

"What doesn’t come to mind is a community of believers in the fullest sense of the word—a biblical community established, not only on the Word of God, but also on the moral laws of God.14 When obedient to our ecclesia commission, these biblical communities will be established not on the Ten Commandments alone, but upon the Ten Commandments and their respective statutes explaining the Ten Commandments and their respective civil judgments enforcing the Ten Commandments and their statutes, adjudicated by biblically qualified men of God who are a continual blessing to the righteous and a perpetual terror to the wicked, per Exodus 18:21, Deuteronomy 4:5-8, Psalm 19:7-11, Romans 13:1-7,15 etc.

"There is not a living person today who hears the word “church” and thinks of what’s depicted in the paragraph above. And yet this description represents the true meaning of the Greek word ecclesia, which has been tragically translated “church.”

"With that, it should be obvious how the word “church” has contributed to the defeat of Christendom—that is, Christians dominionizing society on behalf of their King. Just think what America would look like today if instead we were ecclesias (fully-developed Christian communities) rather than merely street-corner churches...."

For more, see free online book "Ecclesia vs. Church: Why Understanding the Difference is Critical to Our Future" at https://www.bibleversusconstitution.ORG/onlineBooks/ecclesia.html